Reader’s Notebook, 3/11/25

I just read a remarkable book that demands its own post.

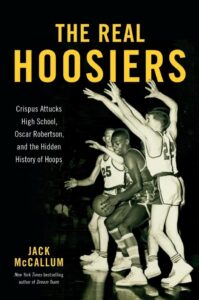

The Real Hoosiers – Jack McCallum

McCallum, the longtime NBA writer for Sports Illustrated, dove into the history of the Indianapolis Crispus Attucks high school basketball teams of the mid–1950s, when Oscar Robertson starred there. Famously, Attucks lost to Milan in the first game of the State Finals in 1954. Milan beat Muncie Central that night for the championship. Their tournament run inspired the movie Hoosiers.[1]

The next two seasons, Attucks lost just a single game on their way to back-to-back state championships.

McCallum begins the book exploring that famous 1954 tournament, pointing out how many elements of the movie were only loosely based on fact, and showing how the historical record has been colored both by the movie and by misperceptions based on the movie. He spoke to Bobby Plump, the Milan star who hit the game winning shot in the championship game and upon who the character Jimmy Chitwood was somewhat based. Plump is a terrific interview and has never been shy about pointing out some of the inconsistencies of both the movie and how people consider those real teams.

The title has a double meaning, though. It’s not just about correcting some of the story about 1954, showing how Attucks was as big of an underdog story as Milan in some ways and that the Tigers upheld many of the hoary principles of Hoosier basketball as well as the rural, white teams did. It is also about examining what Indiana was like in the 1950s, particularly in how African Americans were treated. I had never heard this description before, but McCallum says that Indiana was/is sometimes called the “northern-most southern state, or southern-most northern state,” because of its record of race relations. In diving into that history, McCallum shows us that the “real Hoosiers” were people who were not only reluctant to give African Americans their inalienable rights as US citizens, but even deep into the 20th Century these same “Real Hoosiers” were working hard to keep laws on the books that were insanely racist. As McCallum sadly points out, some behaviors which were common 70 years ago and seem hopelessly retrograde are becoming common again today.[2]

Attucks was built to be the only Indianapolis high school open to Black students, ending what had been integrated schools in the city. It was constructed – and still stands – on the old west side of downtown, an area sometimes called Frog City or Frog Island, that was known for its extreme poverty and lack of basic services. Until the land was cleared for a massive building project in the late 1940s, and continues to today, there were regular outbreaks of cholera and more occasional ones of malaria in this part of town. Guess what demographic group was overwhelmingly forced into this area?

As the city began to clear out Frog Island, the Black families of the area were forced to move elsewhere.[3] But Attucks was still the only high school that their kids could attend. Of course, while the city promised a bussing service for these kids, the money was never allocated for it. Oscar Robertson, for one example, had to walk 24 blocks to school each day despite there being several public schools between his family’s new home and Attucks.[4]

I had never realized this, but McCallum points out how much of the physical history of Black people in Indianapolis has been wiped away. There is no 18th and Vine area, as in Kansas City, where the historical contributions of the Black community are celebrated. Any monuments to African Americans in Indy are scattered around town, just as the people they honor were forced to scatter.

Attucks was one of the few things Black Indianapolis residents could rally around. McCallum both begins and ends the book with a long list of Attucks graduates who went on to do great things, often as the first African Americans to penetrate a particular field. And for a few years in the 1950s, thanks to being home of one of the greatest players to ever step on a court, the Flying Tigers basketball team put Attucks on the map for the entire state.

The 1955 team was the first Indianapolis school to ever win the state championship. Remember, this was in the old, single class system. It only took 44 years for the biggest city in the state to conquer the tournament, which seems crazy. It was also the first all-Black team to win a state championship anywhere in the US.

And the 1956 team was the first Indiana team to ever go undefeated.[5] Ray Crowe, the Attucks coach, was a remarkable man who taught his players both to play basketball better than anyone else and how to comport themselves in a way that wouldn’t cause the team trouble given the era they played in. This book just came out last year, but McCallum was still able to talk to a large number of players on that team, teachers and administrators at the school, and several prominent players who faced the Tigers.

He did not speak with Robertson, who declined his requests. The Big O is a complex, sometimes difficult man, and he still holds a lot of painful memories of his time at Attucks. He was far ahead of his time, a huge guard that the offense ran through but who could also defend every spot on the court and still be the best rebounder. He was LeBron James 50 years before LeBron. Oscar also was arguably the most important player in leading NBA players to gain the right to free agency and control their own careers. He did this before Curt Flood sacrificed his career to challenge Major League Baseball’s reserve clause. For some reason, despite being a much better player, Robertson doesn’t get celebrated for this the way Flood does. Perhaps it is because Robertson was so good that the NBA couldn’t blackball him, thus his career didn’t end when he stood up for players’ rights.

Robertson’s history with the city and state remains strained. He is very much like Michael Jordan in that he never forgets or forgives a slight. He has bitter memories of how Attucks was treated after they won their first championship, which he believes was much more reserved compared to how the general public had celebrated Milan a year earlier. Several of his teammates say his memories aren’t accurate of what actually happened, and the newspaper record from the time shows that some of the things Robertson complained about were based on choices made within the Attucks/Black communities, not things that were forced upon them by the racist city council or governor.

It is hard to blame him, though, given the environment and age he grew up in. Because of all of this, while his name is still held in high esteem here, it always pops up a little later than you would expect when Hoosiers talk about great, local players. Some of that is because he left the state for Cincinnati when he went to college, shunning a recruiting pitch from IU, and stayed in Cincy after retiring from the NBA. When his name does come up, though, no one forgets what a unique and dominating player he was.

McCallum’s story is equal parts delightful, illuminating, engrossing, and maddening. Despite understanding our collective history, it is still depressing and deflating to know that the pre-Civil Rights era really wasn’t that long ago. My father-in-law is two years younger than Robertson, going to high school just a couple miles from Attucks. They are both in their mid–80s, but still, are alive and can speak to that era. And in many states, including northern states like Indiana, it was deep into the 1970s before real change came about. And, of course, our issues with race in this country never really go away, and in fact are being used more-and-more to inflame parts of the population and keep us divided.

Sports don’t solve these problems. But they can give people hope, something to ignore the realities they face daily for a little while, and create a shared pride for a community. That is exactly what Crispus Attucks did for African Americans in Indianapolis in the 1950s.

- The tournament format back in the single days was Sectionals, Regionals (two games), Semi-State (two games), and then the State Finals (two games). This year there were 400+ schools divided into four classes. In the ‘50s, there were over 700 schools playing in a single bracket. Milan had to win nine games, three times playing day-night doubleheaders, to capture their state title. Teams now have to win six or seven, with only Semi-State being a two game day, depending on the size of their sectional and whether they get a first round bye. ↩

- The Indianapolis News newspaper had a section called “News of Colored Folk” in the 1950s. Seriously. ↩

- Today that area is the home of the IU-Methodist medical campus and the university complex formerly known as IUPUI. ↩

- A totally different situation, obviously, but around the same time my father-in-law hitchhiked home each day from old Cathedral downtown to his Broad Ripple area, a roughly five mile trek. Drivers were willing to pick up white, Catholic kids and get them home from school safely. I doubt many of the Attucks kids had that same opportunity. ↩

- South Bend Central became the second undefeated champion a year later, when they beat an Attucks team that still made the finals after Robertson’s graduation. Attucks would win another championship in 1959. In 1986 it was converted into a middle school, then given a second life as a high school beginning in 2006. The Tigers won the 3A state title in 2017. Last week they knocked off #1 Cathedral in sectionals and now have the second-best odds to win the 3A title. ↩